52: Scott Donaton

Source: Adweek

“He beckoned me over to the bed… He had me lean down so he could whisper something in my ear, waiting for a word of wisdom from Uncle Frankie and what he said to me was, ‘I could still kick your ass.’”

About Scott

Scott Donaton is a creative guru, self-proclaimed stand-up philosopher, semi-pro editor of friends’ bios, maker of movements, and asker of poignant questions.

Raised in Brooklyn, Scott studied journalism at St. John’s University, serving as the editor-in-chief of The Torch, the school’s student newspaper.

Scott stormed Madison Avenue in 1996, kicking down the door at Advertising Age, where he made his way up the ranks from reporter to editor-in-chief, serving in the role for over ten years. After grabbing readers by the eyeballs as the publisher of Entertainment Weekly, Scott returned to Madison Avenue as the chief content officer of IPG’s UM global media network. While at UM, Scott was awarded the Cannes Entertainment Lion for original comedy series Always Open, produced for Denny’s with Jason Bateman and Will Arnett.

With trophy in hand, Scott made the move to Digitas North America as Global Chief Creative and Content Officer, heading the agency’s connected creative practice and launching Digitas Studios to create long form content for brands like American Express, Lego, Travelers and Lenovo.

After checking East Coast Domination off his bucket list, Scott moved the party to Santa Monica as the SVP and Head of Marketing at Hulu, where he not only drove growth from 30 million to 48 million paid subscribers, he founded internal agency Greenhouse, pioneered Hulu’s branded entertainment unit, created Emmy award-nominated content, and played a key role in the integration of Hulu into Disney.

In 2023, Scott was elected to NPR’s board of directors, overseeing governance, policies and strategic direction, and likely helping ensure that the storytelling/integrity combo remains strong to quite strong at the esteemed brand.

In addition to Cannes, Scott’s work for brands like Coca-Cola, BMW, Sony, and L’Oreal has been recognized by the Producers Guild of America, Clios, D&AD, and London International Advertising Awards.

-

Max Chopovsky: 0:02

This is Moral of the Story interesting people telling their favorite short stories and then breaking them down to understand what makes them so good. I'm your host, max Tropowski. Today's guest is Scott Donaton, creative guru, self-proclaimed stand-up philosopher, semi-pro editor of FriendsBio's, maker of movements and asker of poignant questions. Raised in Brooklyn, scott studied journalism at St John's University, serving as the editor-in-chief of the Torch, the school's student newspaper. Scott stormed Madison Avenue in 1996, kicking down the door at advertising age, where he made his way up the ranks from reporter to editor-in-chief, serving in the role for over 10 years. After grabbing readers by the eyeballs as the publisher of Entertainment Weekly, scott returned to Madison Avenue as the chief content officer of IPG's UM global media network. While at UM, scott was awarded the Cann Entertainment Lion for original comedy series Always Open, produced for Denny's with Jason Bateman and Will Arnett. With trophy firmly in hand, scott made the move to Digitast North America as global chief creative and content officer, heading the agency's connected creative practice and launching Digitast Studios to create long-form content for brands like American Express, lego, travelers and Lenovo. After checking East Coast domination off his bucket list, scott moved the party to Santa Monica as the SVP and head of marketing at Hulu, where he not only drove growth from 30 million to 48 million paid subscribers, he founded Internal Agency Greenhouse, pioneered Hulu's branded entertainment unit, created Emmy Award-nominated content and played a key role in the integration of Hulu into Disney In 2023,. Scott was elected to NPR's board of directors, overseeing performance, governance policies and strategic direction, and likely helping ensure that the storytelling and integrity combo remains strong to quite strong at the esteemed brand. In addition to Cannes, scott's work for brands like Coca-Cola, bmw, sony and L'Oreal has been recognized by the producers Guild of America, clio's DNAD and London International Advertising Awards. So the stand-up philosophers in the house and on the mic, scott, welcome to the show.

Scott Donaton: 2:10

Thank you, Max. That was fantastic. You tell my career story much better than I do. I think I can take you everywhere or recording of that everywhere with me from now on.

Max Chopovsky: 2:19

Happy to come with you, man. I love me. A good adventure. So you are here to tell us a story. Is there anything we need to know before we get started? Do you want to set the stage?

Scott Donaton: 2:32

No, I can set the stage inside the story itself, I think. So it's probably not a surprise for someone of my age and background to tell you that Godfather, part Two, in particular Goodfellas in a Bronx Tale, are among my favorite movies. Now, what might be more surprising is to know that for me those are not fictional stories. They're snapshots of my childhood and an important part of who I am today. And in fact, goodfellas was not a work of fiction after all, it was actually based on the book Wise Guy. Wise Guy is by Nick Pelleggi, who went to the same high school in Brooklyn that I did, a bit before me, if you know Nick's age, but he's obviously a legend. So I literally grew up in what is now called Carroll Gardens. At the time was called South Brooklyn and when my mother grew up there was considered part of Red Hook second generation Italian neighborhood for the most part, and a lot of first generation immigrants as well. Very much a mafia controlled. If there is such a thing, they apparently isn't, but if there is one, they very much controlled. The neighborhood I grew up in and I'm talking social clubs on the corner where guys named Punchy and Fat Freddy and Big Red hung out all the time with their espresso and playing cards and smoking cigars and gold chains and tattoos, and these were the people that ran the neighborhood and you just knew that and it was a fact of everyday life. And the deli on the corner would sell sweaters in the back. The guy who ran it would say in front of my mother, anna, I got some sweaters that fell off a truck $5 in the back, I'll get some for the kids. This was the truth and I'll say that, while I ultimately obviously didn't face the issue that some of the characters did in Goodfellas and Bronx Tale in other words, I wasn't actually invited into the mob in any way and made other choices there was definitely a period where that was a very romantic way of living. There was a very romanticized view of the neighborhood. By the way, I grew up being told how safe I was in my neighborhood. Of course, I realized later on that was because of the color of my skin and the fact that I was one of them a very tribal neighborhood, and most of the neighborhoods in Brooklyn were. At that time, I knew which neighborhoods and streets I couldn't cross over into, but these guys seemed really cool. They literally had the cigarette packs rolled up in their t-shirts, and the tattoos and the gold chains and swaggered around the neighborhood. And it took me quite a while, and without much putting judgment into this, to realize that these were not people I wanted to emulate or base a life off of. But my family itself was a very blue collar one, a lot of cops and firefighters and long shoremen. We had a brownstone in that neighborhood that had probably had about 80 cousins and second cousins and third cousins. Of course they were all just cousins to Italians who lived within a five block radius, and on Christmas Eve we would all gather in the same brownstone that my grandmother lived in and there'd be 80 or so people running up and down across four floors all night long doing the feast of the seven fishes, my Italian great grandmother, who signed her name with an X and couldn't read or speak English, but when I'd be outside in the streets playing stickball or running bases or Ringolivio was the name of a game that we played on the streets of Brooklyn the ice cream truck would come and my great grandmother would wrap on the window the third floor window of the brownstone, until I paid attention to her, whether I wanted to or not, and then roll up the window with lots of paint flakes falling to the street and toss down a crumpled dollar bill which meant go get me a vanilla cone with rainbow sprinkles, and then I'd have to carry her cone in mine up the steps dripping down my arm. Scotso, she called me because she didn't like that. My mother gave me an Italian last name, and this was just really an amazing way to grow up in so many ways, and while there are so many things about it today that I can see that are really flawed, my mother sat on the brownstone, stooped every night with her cup of coffee and we all played late into the night while our mother's gossiped over the walls and the wise guys played cards on the corner, and some of this comes down to me. I had an uncle, frankie, who was a longshoreman and he was like a father to me and he was very much a kid of the streets and covered in tattoos. He didn't want to be on the wrong side of his temper and he was the tough guy and he showed me a view of masculinity. And when he was a little bit older he had a quadruple bypass and if you've ever seen somebody in a hospital after that procedure. They don't look good. So I went to the hospital to visit Frankie and he was very thin and frail looking tubes coming out of everywhere. Really terrible to see him this way and I swear this actually happened. It sounds like a scene from a movie, but he beckoned me over to the bed and I got over and he had me leaned down so they could whisper something in my ear and I leaned down and waiting for a word of wisdom from Uncle Frankie and what he said to me was I could still kick your ass. So this is the world that I grew up in and this is the thing that I think people most love about me today. I will say the Brooklyn accent. Some people hear it in trace form still, you know. But if you want me to do the whole interview like this from the from here forward, I could just kind of bring it out and we could do it the rest of the day, all day long. When I go back and visit my family at Christmas, I'll find myself I'll go to the bagel store and I'll be like yo, chief, give me, treat them everything bagels. And I'm like who was that? What's going on in there? That was Scott. You got a not wise guy wise guy with you today.

Max Chopovsky: 8:08

That's amazing, the way that you painted the picture of that block, with the wise guys playing cards on the corner and the moms gossiping and drinking coffee while the kids played into the night. It's such a vivid picture and that's probably why you remember it so vividly that when you tell that story, it's such a time-wist neighborhood too, because I was there a few weeks ago and it's been completely gentrified now.

Scott Donaton: 8:34

There's still traces of Italian there. There's actually a couple of bakeries and restaurants that were there since I was a kid, but the streets haven't changed. The brownstones have been updated because they were crumbling, but it's really a beautiful tree-lined neighborhood that retains as much of that character today as it always did, and I think that's the beautiful thing about Brooklyn.

Max Chopovsky: 8:54

I think it's such a joy to grow up there, because it really is a special place it really is and, by the way, I could tell the Brooklyn accent, because the dead giveaway is the Rs sound like Vs and it's a Brooklyn. That's immediately noticeable.

Scott Donaton: 9:13

Yeah, I like to think it's gone. I never took conscious steps to take it out, but I think I, just as I got exposed to more of the world and more people and moved outside the limits of the neighborhood, it mostly went away. It definitely comes out when I'm angry or excited, but it does come out when I'm around my family in ways that scare me sometimes as well.

Max Chopovsky: 9:33

Totally, yeah. I mean, I think that when you go back to where you came from, whatever you tried to repress or suppress in some way, it just bubbles back to the surface. Like if I go back to Kentucky to see my family, there are times when I notice a very slight, vague Southern accent. I'm like, oh my God, who is that person? I haven't talked to that person in a while.

Scott Donaton: 10:03

I'm still friends with four or five guys I went to high school with and we have very different lives in a lot of ways today. Some of them still live in the same neighborhood, but we get together about once a year for dinner and, to your point, like you can't be anyone but yourself with those people. They don't care what you've done since then, they don't care who you think you are now, like you are the same person they grew up with and they will take no bullshit from you.

Max Chopovsky: 10:28

Totally. Now let me ask you this as you're walking into this hospital room and Frankie is laying in the bed, do you have any idea about what he's about to say? Like, do you feel like it's going to be some timeless wisdom? Are you imagining that some words that you can't repeat will come out of his mouth, like where's your head at when this is happening?

Scott Donaton: 10:51

First of all, it was really hard walking into that room because he was one of the most vibrant people I knew and, by the way, he came back from that surgery. He's since passed but died. I hate the word passed, sorry, but I was really worried at that point. I didn't see that he was going to survive what was happening here and he really was like a father. I had a father, who's also died, but Frankie became a real kind of second father to me in a lot of ways and again showed me a very different view of masculinity than my father, and not one that I emulated, necessarily, but one that I saw up close through him. But he had this kind of fierce Italian love and even when I was getting married he called wife to be over at a dinner one night and sat aside with her and later on she told me that he basically said if you break his heart, you're going to have to answer to me. That's my son over there, that's my son. So I really thought he probably would just say something like you know you're my son and I know how much I love you. And the fact that he said like it's still kick your ass. He actually just said I still kick your ass. He didn't say could. I was clean, I was making the sentence a little more. It was kind of brilliant so character when it came out that I was like what else could he have said to me in that moment? He did not want me to. He probably saw somewhere in my face which is not something you want to show to people in that place, the concern about seeing him like that, and I think he did not ever till the end to want to be viewed as anything less than than the fierce, tough guy he always was.

Max Chopovsky: 12:26

Do you think that he figured those were going to be his sort of last words to you?

Scott Donaton: 12:31

Maybe, maybe, although I don't know if he would have admitted to himself that he was ever going to die.

Max Chopovsky: 12:37

Yeah, totally. You mentioned that he gave you a different perspective on masculinity than your dad did. How did the two perspectives compare?

Scott Donaton: 12:48

My father was much more God. It's weird, I'll just. The first word that comes to my mind is timid. There are people who know him. He's a big guy and he could be a loud guy sometimes but he wasn't forceful, and he with his second wife in particular. And I realized as I got older to not to make this into a therapy session but that I had kind of in some ways made him a little bit, even cartoonishly, the opposite of Frankie, but it felt like a lot of times. You know, his ex-wife was really the one who ran things and my father went along with them and didn't push back on a lot of things. He also he wasn't very expressive. He didn't say I love you a lot. He didn't want to have big conversations about, even as I got older, like the impact of the divorce on me or any of those things were just not topics he felt comfortable with and Frankie was just very expressive, very, constantly hugging, constantly touching, showing his love. But he was also someone to be afraid of. I used to think there was a period of time when I was younger where I might have made a bit of noise chewing my food, and there was not. You know, there might have been one or two times that I ended up finding myself out of my seat on the floor after doing that too loudly for too long in front of Frankie. So you know, it was very much a. You're the man of the family, you're in charge, you take care of things. You don't let anybody push you around. You get into a fight if somebody messes with you. I had a short temper for in my twenties not a violent one, but a short one, and thankfully I don't anymore. It didn't serve me, but it was interesting. I realized much later in life how much these, the contrast between the two of them, left me feeling like I had to figure out on my own what it meant to be a man and what kind of man I wanted to be.

Max Chopovsky: 14:36

Because they were basically opposites of each other.

Scott Donaton: 14:39

Yeah, for sure, there were some stories. There was a story where there was a bit of a conflict between them, which was almost going to be my story for today, but it really came out of that and my father was definitely afraid of Frankie and probably should have been.

Max Chopovsky: 14:55

I believe that, based on how you're describing them Now, you mentioned that you were not in the mob Did they ever approach you? Did they ever try to recruit you, or what was that process like? How did that even happen, if they did?

Scott Donaton: 15:10

I don't recall anything on those lines. I mean, there were definitely times when they'd see you go into the deli and they'd be like get me a bag of chips or a soda. We knew them. Some of them were fathers of my friends that I was playing with on the block. We were respectful of them. They would occasionally just give you money for no reason or ask you to run a favor, and maybe for some others that becomes a gateway that if you push against, it opens. I don't recall that I ever pushed against it, but it was just a. You know, it is funny when I do watch a Bronx Tale in particular like it's really hard not to be like for so many people. I think this is like this world that didn't actually even really exist and it so did in almost exactly the way that it's portrayed in those films that I'm almost like how did I get out?

Max Chopovsky: 15:59

and why so those are accurate, the way that they're portrayed, done in those films.

Scott Donaton: 16:03

Yeah, I mean Goodfellas and not the Godfather. Amazing a film as it is. I don't think it's meant to be grounded in reality, but I think Goodfellas and a Bronx Tale for me feel like really known places and people.

Max Chopovsky: 16:16

It is kind of, you know you use the same word that I was thinking of which is romanticized. It does feel like, especially in hindsight, to be a really romanticized time where things were difficult but also simpler in a number of ways, you know, and now that the world has gotten so much more complex and globalized and technologically advanced and all of these different things, there is, I think, a part of some of us that kind of feels this, maybe yearning or sort of melancholy towards those times, you know, when things were just, I guess, a little bit less complicated.

Scott Donaton: 16:55

Yeah, I think for sure, and I'm not nostalgic per se, maybe I am. I'm definitely a bit of a romantic around things, but I still see, you know, brooklyn through, you know, a lens. That doesn't mean my view on it and some of the people and not again, hopefully not in a judgmental way Even some of the kind of again I use the word tribal, which maybe in some settings would sound judgmental, but like there was something about people who just kind of this is where I was born, this is where I'm gonna die, this is my family, they're what matters to me. Me moving cross-country was even an older, later age in life, like to my mother on some level. You know I was leaving and there are things about it that I definitely came to appreciate, you know, and even the blue collar aspect. I think I was the second person in my family to go to college and you know there were times when I think sometimes even they thought like, oh, mr, college the great. But like these are people who worked hard their entire lives to care their families right, who there's so much that I admire about it, even when I see it through a clearer lens, that definitely can rub away some of the romanticized view. You know, some of these wise guys were not good. They were not good people right, and they didn't do good things and there's no world in which pretending otherwise makes sense, but so justifying none of that. But you know, there was a guy in the neighborhood who was only a few years older than us, I think, and his name was Artie Boy. And you know, like Artie Boy had these big colorful tattoos of devils and again, he was the one you know always had the cigarette pack rolled up. It was hard not to think that was really cool. A knife in his back pocket. It was hard not to see that as cool when I was a kid and easier to see it as not cool now. But I still understand the attraction at the time. I mean the fact that there have grown men with names like Big Red and Punchy and Fat Freddy. You know, and this is real, it's kind of awesome.

Max Chopovsky: 18:52

It is kind of awesome.

Scott Donaton: 18:53

Yeah, it is kind of awesome.

Max Chopovsky: 18:54

To a storyteller yeah, so tell me this the story that you told. What is the moral of that story?

Scott Donaton: 19:00

It's funny. I even not that I don't know what Dord moral is, but knowing the name of the podcast, I was like what is the moral of the story? And I do think it's kind of embrace who you are and where you're from. There was someone that I mentioned that I might share this story, who was like do you want people to know this about you? And there's another guy that I know in the. He has his own ad agency. He's done really well in life and he grew up in a very tough family not in Brooklyn, very similar circumstances. He grew up very poor. I definitely we were struggling financially when I grew up. I mean, we had government cheese in the fridge and food stamps and you know. So I know what that's like. And I think there are times when I've met throughout my career so many people who had much different upbringings. And there are times where I've, you know, the temptation would be that somehow this is something that you should hide about yourself. I'm so proud of it because it is. It played a huge role in the person I am today and I think it's like it's all part of your story and no matter what your story is, and the more you tell your story to more people, which I'm sure, to some degree, is what drew you here, the more you've realized how universal so many of our truths are and I think, like never forget, like where you came from and how that made you who you are today 100%.

Max Chopovsky: 20:20

We also, after we moved to America, we also grew up on food stamps and we didn't really have very much. And I think that and again, this is just my theory I think that what happens is people want to downplay that because they want to either assimilate or fit in, or they want, or they think that that's a knock on them as a person. You know and their character and ultimately part of the reason that some people that started with nothing became successful is because they had their back against the wall and they had to learn how to grind at a young age, right, and it's not until we become older that we not just recognize that, but we embrace it and it really starts to come out and we become more proud of where we came from, because it had so much to do with where we ultimately end up in life.

Scott Donaton: 21:20

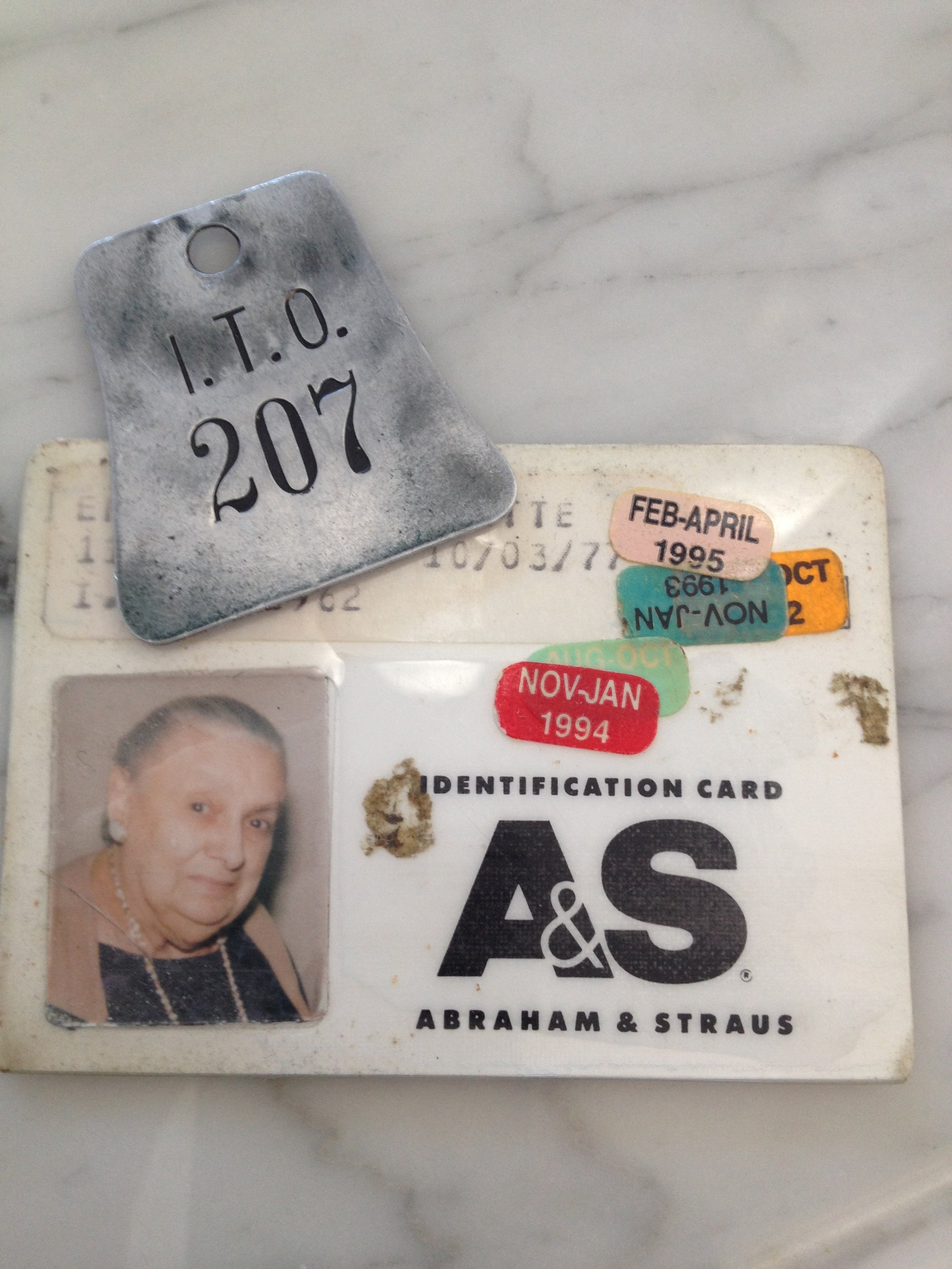

And I wouldn't want it any other way. I mean, to your point, I've been working since I was 12. It started with two. I had two paper routes. The New York Post was an afternoon newspaper then, so I would deliver the daily news by bicycle before I went to school, and then the New York Post after I got out of school. I worked stocking shelves in the grocery store in the corner and I drove a delivery truck when I got a little older for a butcher shop whose the horn on the van played the Godfather theme song and I used to start my Saturday morning deliveries and make sure that I blew that horn on certain blocks, which I'm sure there are still people there who like that damn horn. That woke me up every Saturday morning. But it is all part of who you are and the high school I went to. If you know the TV show Welcome Back Cotter I'm really showing my age here now, but the high school that's shown in all the exterior shots for Welcome Back Cotter is my high school and the sweat hogs and all the things in there is John Travolta. The show that made John Travolta were based on my high school and that did feel like something almost to be ashamed of for some years, and now it's something I couldn't be prouder of.

Max Chopovsky: 22:24

Totally. I think it's only something that we can appreciate when we're older. Right being able to embrace that is so important. So you obviously have a ton of stories that you've heard and told why did you choose this one? It was between this one and another one you mentioned earlier. So what made this one went out?

Scott Donaton: 22:45

Yeah, there were three. I mean that made the final cut and I think what I worried most about with this one was that it's not actually one story in the way that some of the stories that I've heard from others that you've interviewed is, and I was a little afraid that it was painting a whole picture of a childhood, as opposed to each of the other stories were kind of much more particular moments or days, but I think it's because I felt this one, at the end of the day, best represented me and who I am.

Max Chopovsky: 23:15

There are sometimes these singular moments that just encompass an entire era right and in your mind, that moment was just representative of that entire picture that you drew in the beginning of the story.

Scott Donaton: 23:32

Yeah, yeah, I think so. If you want to know the headline of one of my other stories, I won't go deeper because one of the other truths is it doesn't go much deeper and it's not that interesting at the end of the day was I once spent the night in a hotel room with Bill Clinton? Oh, that's amazing. Yeah, but it's not as good a story as it seems. I mean, it's not a bad story it was the night that Hillary was elected to the Senate. I ended up at a celebration party in their hotel room.

Max Chopovsky: 24:02

I actually feel like the best way to tell that story is just to leave it at the headline, because I should have. Yes, people's imaginations just run wild, so you've obviously heard a ton of great stories. What do good stories have in common?

Scott Donaton: 24:18

They have to have some kind of tension and conflict. What's really interesting is, having spent a lot of my career doing storytelling for and with brands, it's amazing how uncomfortable that makes brands that always want to present a happy view of the world. But I think one of the first things whenever I'm helping a person or a brand the people who work for that brand to figure out what their story is. There's three things there's kind of like with all love to Simon Sinek to start with, why is my favorite Ted talk of all times? I've told him that whenever I meet him I fanboy out on him a little bit and I repeat that to him every time. But it became a driving mantra is kind of know your why, which maybe goes back to what I said that I think the moral of this story is. But the other two to me, things that you have to have to have a great story is you have to have a tension and a conflict. You have to have a monster that you're slaying. Again, when you talk to companies it's always interesting. You're like you say who's your enemy and they go if they name their competitors and you just go no, no, no. Mikey's enemy is the couch right, snickers, enemy is being angry, right and like, and any good story. You need an enemy, you need a point of tension and hopefully you have a hero and maybe they win, maybe they don't, they don't have to. The best stories often are the ones where you don't get the ending you expect, obviously. And you talked about painting a picture. I think writing is where I really best express myself and whenever I write about Brooklyn, even just in things for myself, I really try to capture all of the color, because I can still hear that window pain rattling up in my great grandmother's window and I can still see the brown paint flakes falling down onto the street and that crumpled dollar bill and I could still picture her house dress and I can see her hands and like. In a great story you bring all of that to life for someone.

Max Chopovsky: 26:15

Totally, that's what I was thinking of is the paint flakes, because that it's like the small details. And what's cool about verbal storytelling, or even written storytelling, is that you leave it to the audience to create the picture, to recreate that scene for themselves.

Scott Donaton: 26:36

Yeah, so it's always that thing. I'm a very avid reader when I don't think you can tell good stories unless you read and consume stories all the time as well. But whenever the book is made into a movie, it's always that moment of like that's not the reality that I pictured, which is also why I love like Goodfellas, for example, because like that one like totally nailed it for me from the book. But there are others where you're like that's not what that guy looks like, because that great story you knew, you saw the house, you saw the person, you saw the in book form, which is always a danger when someone suddenly casts Tom Cruise on the role and you're like no, no, no, no.

Max Chopovsky: 27:13

No, you had it all wrong. So stories got to have tension. It's got a paint-a-vivid picture. Do you feel like every story has to have a moral? And if it doesn't, is it still a good story?

Scott Donaton: 27:26

That's why I looked up the word moral when I was doing this, to figure out if the story I was telling did have a moral Intent versus interpretation is something that I'm fascinated with, and whenever I meet artists from any medium, I will ask them, if I have the opportunity to, how hard it is to let go of their work to audiences, to the public, to whoever, when they're done with it, to others, and how much they care about whether they're trying to deliver a specific message within their story versus being completely happy that once they let it go, it's not theirs anymore and it's up to whoever sees it, reads it, hears it to interpret and take meaning from it. And I just find that's a space that fascinates me, and I think it goes to the question you just asked, which is like maybe it's not so important that every story has a moral If it's the storyteller saying what that moral is. Maybe it's just important that anybody could hear any great story and take their own lesson from it.

Max Chopovsky: 28:26

Yes, I think that's the Holy Grail is a story that you are not cramming down people's throats. It's a story where every person can take away their own moral.

Scott Donaton: 28:39

And hopefully it resonates with them, hopefully they see themselves in it. I used to read a lot of fiction way back when I was married that well I still do, but that my ex-wife would characterize as dark and sad or you know, whatever you read, all that dark, sad stuff. I don't like that and I would say it's funny. I don't see any of those stories as dark and sad because they make me feel less alone in the world, because these people have taken their worst things, their most shameful things, their most painful things and they just put them out there for all of us to see and make you realize you may have this thing inside of you that you somehow attached darkness to, but you're just a human and like that's. I would find those stories uplifting in that way and I remember just feeling completely disconnected from the fact that she saw these as dark and sad and I was uplifted by them.

Max Chopovsky: 29:30

Well, you know, rick Rubin would have a lot to say on this matter. He would say that, as an artist, you have an obligation to release your art into the world and your loyalty is first and foremost to the art, then to yourself and then to the audience, which implies that the audience should be left to their own devices in determining what the moral is, but it also implies that everybody will draw a conclusion, whatever it may be. And he talks about how, at the end of the day, the way that you felt less alone when you read some of these stories that she would call dark, you found a connection to those stories. And as long as the person, the reader, the audience, finds a connection to the story, it ultimately helps them feel less alone and it sort of fulfills one of the main premises of storytelling, which is it brings us all together, as you know, as as Gotta connect us, yeah.

Scott Donaton: 30:36

Yeah, it's got. They have to connect us and I think this won't be the first time in my life that I've said the sentence. If there is a second chance at life on this planet, I want to come back as Rick Rubin Amazing, amazing person. But you know I go to Burning man every year for the last 12 years. I didn't go this year because I had to be in Scotland for a family wedding. But there was a year when I was invited by an artist. She had created this amazing experiential piece and it hadn't opened yet and it was about two days into the festival. There were some technical and mechanical things that were being fixed and I got invited to be part of the team that came in and helped test everything before they opened it one night. And then there was a. We were there and it was kind of roped off still and they got everything going. We tested it, it was all ready to go and there were probably 200 or so people kind of just milling around the perimeter of this thing waiting for the perimeter to drop so that they could experience it. And the artist, her team, was like we got it and she was like let's do a champagne toast. And she gathered everyone and I kind of stayed on the edge because I wasn't part of the core crew, I had just come for this last part. She kept making speeches, she kept calling people out in the toast and her team was kind of gently saying like hey, we have to drop the rope. And she finally looked up and she said I know I've been delaying the moment because the minute that rope comes down it's not mine anymore and I just love that. That's where I became. I started really articulating this idea of intent versus interpretation, and what is it like for an artist to let go of their work?

Max Chopovsky: 32:07

It is a I think, I feel like it's an emotion that's at once painful, exciting, filled with trepidation and a shit ton of anxiety.

Scott Donaton: 32:23

Yeah, and every once in a while I've asked an artist who's been like oh, I don't have any complex feelings about it at all. I was like, okay, which is their truth, which is fine. Obviously I think Michael Stipe was the one who used to people asked him what his songs meant said whatever they mean to you is what they mean, and it may not be if it was awesome. If it wasn't awesome.

Max Chopovsky: 32:42

whoever said it Totally, and some people are more ready to let go than others. So you mentioned books a few times. What is one, or what are a handful of your favorite books that just nail storytelling?

Scott Donaton: 32:57

Yeah, I mean again, this is reflective of my age and background and my reading tastes have gotten so much more diverse now, in large part because I think we have an opportunity to. There's so many more diverse stories being told finally by so many other voices, or at least in this country, and being exposed to the highest levels of winning top book awards and so a lot of writers that I'm reading now that might be Indian or Chinese or writers who are telling a story, or indigenous reservation dogs, by the way, not a book but like the TV show, amazing telling of indigenous stories. But I grew up on and loved John Updike and John Irving and Richard Ford and Hemingway and they were all white men. But I think again, I got married young and I talk about this upbringing and I think probably the rabbit series from John Updike, starting with Rabbit Run with a guy who literally wanted to run away from his life and his marriage and there was a lot of that kind of suburban dystopia in Updike's writing from the point of view of the man, always. Obviously I don't know why I'm being apologetic about one of the greatest writers of all time, but Philip Roth as well, and even something like Sabbath Theater, which I can't ever pronounce properly, is just like the complexity of the emotions and the dark and worst impulses that can bubble up in people sometimes and like these are all among the books that really kind of helped me to see myself. But I also have certain books. I just started rereading Catcher and the Rye for probably the 12th or 15th time. I read the Kill a Mockingbird every couple of years. I read Catch 22 about once a decade. So I think and this is probably true for a lot of people around my age in particular Catcher and the Rye is the book that taught me how to read, like I had a great English teacher, I should say he taught me how to read, but that was the book that he really taught me how to read in beyond the words that I was seeing on the page. I remember even I think there's a character who is Holden Caulfield's roommate and his name is James Castle, and coming to the realization that he was JC, he was Jesus Christ and he had died for Holden's sin, and it's just like there are some things that just really that book, probably more than any, is seminal in my life.

Max Chopovsky: 35:23

Totally Last question for you. If you could spend a few moments with 20 year old Scott and say one thing to him, what would it be?

Scott Donaton: 35:37

Get over yourself and don't believe your own bullshit. I think in my maybe not right at 20, but certainly into my early 20s Like I wasn't totally cocky, but I think I came across that some people was arrogant. I also think I was judgmental. I know I was judgmental. I'll switch my answer slightly. I'd probably be like don't be judgmental, because I remember the moment and this is again seems obvious. But the thing that finally, I feel like almost in one moment, broke for me being judgmental was when somebody just gave me the simple device of two things. One is, whenever I look at someone and I find myself about to judge them, I stop and say what is it about them? That is triggered a fear for you, about yourself, myself? And the other thing is just to say that's me, he's me, she's me. Yeah, I think if I could teach him any lesson, it would be they're all you, you're all them.

Max Chopovsky: 36:32

That's really good. You know, I'm really hard on myself and I was listening to this podcast. I think it was Peter Atia and he mentioned this in his show. He said you know, when you're really hard on yourself and you have this really critical internal dialogue, self-critical internal dialogue you should talk to yourself the same way you would talk to your best friend who just did the same thing that you're so mad at yourself for, and you will immediately notice the stark difference of how you talk to yourself versus how you talk to your friend. And if all you do is notice that, it's already a success. But it then makes you just realize how hard you are on yourself. And when you're talking about being judgmental, it's so interesting you can just say, well, that's me, how would I talk to myself?

Scott Donaton: 37:25

Right, yeah, no for sure I will find myself. If a friend of mine is beating themselves up, I'll just say you know, and I'll use their name. Like you know, don't talk to my friend Aaron like that. I'll say to my son like, don't talk to my son Jack like that. Right, I love him. I will not tolerate you talking about him that way. It's a good. But I just want to thank you actually for that question, because I didn't like it and now that I just stumbled into that answer while starting somewhere else, I'm okay with that question. I'm like oh, that's it, I have an answer. Now it may evolve, but right in the me of today, that's my answer and I like it.

Max Chopovsky: 38:02

Sometimes you have to wade through discomfort to get to a prize on the other side. The only way out is through. The only way out is through. Well, that does it. Scott Donatan. Stand up philosopher.

Scott Donaton: 38:18

Thank you, that's Mel Brooks. Mel Brooks is mine.

Max Chopovsky: 38:23

But you use it, I do, there's nothing wrong with that. Thank you for gracing the mic and being on the show man. Thank you for having me Max.

Scott Donaton: 38:31

This was really amazing, delightful way to spend time.

Max Chopovsky: 38:35

Well, thank you, I appreciate that For show notes and more head over to maspodorg. Find us on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, wherever you get your podcast on. This was Moro of the Story. I'm Max Trapowski. Thank you for listening. Talk to you next time.